12 Case based surveillance

A case-based surveillance system focuses on identifying persons that have been diagnosed with an infectious diseases. A person diagnosed with a disease is called a case if the appropriate definition is fullfilled See the classification stage. Case-based surveillance is the most important type of infectious diesase surveillance.

12.1 Terminology

A case-based surveillance system is also called an indicator-based surveillance1 It is called indicator to convey that the focus lies on the compilation of indicators. The term case-based surveillance is - in the eyes of the author of this book - more accurate as it puts the focus on the event under surveillance which distinguishes it from other types of surveillance systems. Other surveillance systems also compile indicators e.g. the viral load in wastewatersurveillance. The CDC usually describes the concept as a case surveillance but less frequently also as a notification-based surveillance system2. This type is sometimes refferd to as physician-based surveillance or lab-based surveillance when physicians or labs are the main provider of information.

12.2 Process of a case-based surveillance system

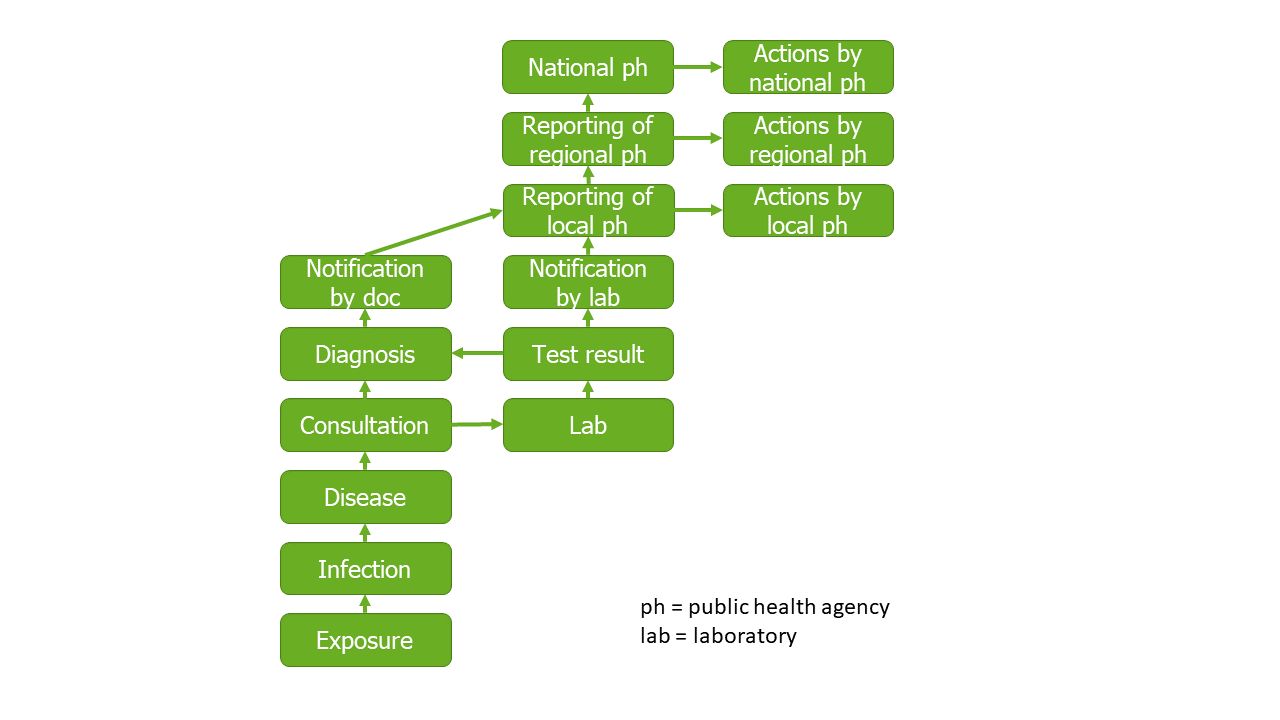

As case-based surveillance is normally mandated by law, the objectives are often laid down during the legislative process. A typical process is that a physician is required to fill out a form when she or he finds a person that has a disease. The form is then send to a local public health agency where the event is collected and classified. The local public health agency takes appropriate measures and enters the data into a software. This data is transferred to regional or national levels where experts analyse the data for the reporting and supraregional measures.

12.3 Strengths and weaknesses

Strengths:

- measures one central event in infectious diseases directly - allows case-based measures - allows collecting detailed information e.g. on exposure or demographics - usually allows the measurment of the severity of a disease (e.g. hospitalisation)

Weaknesses:

- usually goes along with a strong selection bias, especially in disease with a many asymptomatic cases - expensive - depends on a reliable health system

12.4 Example of a case based surveillance system

The German infectious disease reporting system is governed by the Infection Protection Act (IfSG). It is the backbone of epidemiological surveillance in Germany. It has developed historically and has its roots in the Imperial Epidemic Act of 1900. This act hat for example the following regulation: “Any case of illness and any death from leprosy, cholera (Asian), typhus, yellow fever, plague (Oriental bubonic plague), smallpox […] must be reported immediately to the competent police authority.” The current reporting system was established in 2000 with the creation of the Infection Protection Act. The reporting system is legally regulated in Sections 6 to 11 of the Act, which have been amended multiple times, usually in response to acute events such as the HUS epidemic in 2011.

The events (Stage 1) monitored are typically the occurrence of infectious diseases. However, the reporting system encompasses various reporting obligations and multiple reporting channels. It can therefore be viewed as a collection of related but essentially different surveillance systems. A significant component of the reporting system is the obligation for physicians, pathologists, and other professionals to report. The event captured in this context is the suspicion of a disease, the diagnosis of the disease, or the death from a diseases. The infectious diseases are laid out in the text of the law and consists out of severe diseases that can be medically diagnosed, such as measles, polio, or HUS. Another relevant component is the obligation for laboratories to report. The monitored event is a laboratory finding indicative of an acute infection. This laboratory reporting obligation applies to a wide range of infectious diseases. In addition to the physician and laboratory reporting obligations, there are other components, such as non-nominal reporting obligations for the laboratory detection of certain pathogens like HIV, which follow a separate reporting pathway.

The capture of physician and laboratory reports (Stage 2) is usually carried out through the reporting process and investigations by the health authorities. For many years, the method of reporting was not standardized and was typically done via fax. In the last decade, the German Electronic Reporting and Information System (DEMIS) has been developed, primarily digitizing the reporting process from the reporter to the health authority. This method of reporting is now legally required for many reporting channels under the Infection Protection Act. The way health authorities conduct investigations is not prescribed, although there are, of course, restrictions due to privacy rights. A common investigation involves a phone call from the health authority and an infection control interview with the affected individuals. The reporting system is thus a hybrid system of passive and active surveillance. It is passive because the monitored events do not exist solely because of the reporting system. For instance, in most cases, a laboratory test is performed for clinical reasons, not for epidemiological reasons. It is active because health authorities actively investigate and contact the affected individuals. Investigation is a central part of the job profile for public health inspectors.

The classification (Stage 3) within the reporting system is performed by the health authority, assisted by the respective reporting software. After entering the collected data, the software indicates whether the event matches the defined criteria. These definitions are twofold: first, there is a definition for events that must be reported to the state authority and the RKI (“reporting definition”), and second, there is a definition for cases officially counted in the RKI statistics (“reference definition”). Establishing these definitions is crucial for ensuring comparability and identifying increases or decreases in the number of cases. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese government changed the case definition of COVID-19, leading to an artificial spike in the statistics. Case definitions can be sensitive, aiming to capture as many cases as possible, or specific, aiming to include only a small number of false-positive cases. Case definitions exist not only for a surveillance system but are also often established separately for outbreaks. Additionally, case definitions are not necessarily the standard for implementing measures. For example, in a suspected case of hemorrhagic fever, action does not need to wait until a case definition is met.

Data management (Stage 4) takes place after classification. The reporting system has significantly benefited from more professional data management. Before the introduction of electronic reporting software, data was transmitted laboriously and prone to errors via mail or fax. With increasing digitization and the reduction of media disruptions, data management has become increasingly precise and faster. The most well-known reporting software, SurvNet, from the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), sets the standards for transmission from the health authority to the state authority and from there to the RKI. Data management is carried out in databases operated by the RKI. This process includes quality assurance and data preparation for the subsequent evaluation stage. The preparation also involves automated signal detection, identifying and appropriately displaying potential outbreaks.

The analysis of the reporting system’s data occurs at all three levels: local, state, and national. This is similar to the interventions taken. Usually the local agency takes case based measurements, whereas the state and the nation take population-based measurements